Kali

As most of north India celebrates Diwali, Bengal will be worshipping Kali. Why is this so?

Kali is the form of the primordial Mother Goddess which symbolizes Shakti – Power -- as well as Destruction. She has Her origins in India's archaic matriarchal culture. Her radiant blackness came from the dark-skinned tribes who worshipped Her to instill fear and dread in their enemies. She was worshipped with blood sacrifice, and offerings of flesh and liquor. She was All-Powerful, awesome, mysterious as the night, fierce, the sensual and demanding Mother, also an all-merciful Protectress, the Cosmic Female Power, always available for Her devotees, ready to remove their suffering, their fear of time (Kala), who lived in the burning ghats, ready to receive her children back into her womb at the funeral pyre.

Hear me child, and know Me for who I am. I have been with you since you were born, and I will stay with you until you return to Me at the final dusk.

I am the passionate and seductive lover who inspires the poet to dream.

I am the One who calls to you at the end of your journey. After the day is done, My children find their blessed rest in My embrace.

I am the womb from which all things are born.

I am the shadowy, still tomb; all things must come to Me and bare their chests to die and be reborn to the Whole.

I am the Sorceress that will not be ruled, the Weaver of Time, the Divulgeress of Mysteries. I snip the threads that bring My children home to Me. I slit the throats of the cruel and drink the blood of the heartless. Swallow your fear and come to Me, and you will discover true beauty, strength, and courage.

I am the fury which rips the flesh from injustice.

I am the glowing forge that transforms your inner demons into tools of power. Open yourself to My embrace and become part of the light that is in the darkness.

I am the glinting sword that protects you from harm.

I am the crucible in which all the aspects of yourself merge in a rainbow of union.

I am the velvet depths of the night sky, the swirling mists of midnight, shrouded in mystery.

I am the chrysalis in which you will face that which terrifies you and from which you will blossom forth, vibrant and renewed. Seek Me at the crossroads of Life and Death, and you shall be transformed, for once you look upon my face, there is no return.

I am the fire that kisses the shackles away.

I am the cauldron in which all opposites grow to know each other in Truth.

I am the web which connects all things.

I am the Healer of all wounds, the Warrior Mother who rights all wrongs in their Time. I make the weak strong. I make the arrogant humble. I raise up the oppressed and empower the disenfranchised. I am Justice. I am Mercy. I am the End, and in that I am also the Beginning.

Most importantly, child, I am you. I am part of you, and I am within you. Seek Me within and without, and you will be strong. Know Me. Venture into the dark so that you may awaken to Balance, Illumination, and Wholeness. Take My Love with you everywhere and find the Power within to be who you wish.

Ur-Kali as a primal female principle can be found in many ancient cultures outside India, suggesting that in the distant past a common or related matriarchical religion pervaded much of the world. In pre-christian Ireland people worshipped a powerful goddess known as Kele (her priestesses were known as Kelles), from which the surname Kelly is descended. In ancient Finland there was the all-powerful smelly goddess of death and decay Kal-ma, and in the Sinai region of the Middle East there was the goddess Kalu. Kalu was associated with the new moon or amavasya -- lunar periods were called kalends in the ancient Mediterranean. This is one of the origins of calendar. It is likely that these are the result of the interplay of spiritual ideas and practices between India, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete and Greece before 1500 BC.

With Aryan and thereafter Buddhist dominance, dark Kali was the goddess of defeated peoples. She remained, however, in the substratum, part of the aboriginal demonolatry and the Tantric occult, and slept on in the names of places like Vajrajogini. The current representation of Kali is relatively new. In the 15th-16th centuries, the flow of the Ganges shifted towards East Bengal, via the Padma to the Bay of Bengal; this opened up a new settlement frontier to which were attracted itinerants – who tended to be from the ‘lower’ social strata than the Brahmano-Buddhist establishment. At the same time, Muslim power in Bengal changed hands from the Afghans to the Mughals. This consolidation of a foreign religion cut off the Brahmanical religion from state funding; the Buddhist establishment in Bengal had been destroyed earlier by the Afghans. As Aryan and Buddhist dominance receded, Kali emerged from the subterranean cultural memory of the slash-burn pastoralists, the hunters, the woodsmen, the tribal smiths and stonesmen who flocked to the new Bengal frontier.

Some of the aspects of Kali also reflect the despair felt at the Muslim consolidation. Thompson and Spencer in their Bengali Religious Lyrics say:

"The worship of Durga and Kali is perhaps most deeply rooted in Bengal, as has already been indicated. I think it would not be hard to find reasons for this. Take the case of Mukundarama, known as Kavikankan or 'gem of poets,' who finished his chief poem, the epic Chandi in 1589. This poem lives today mainly for its value as giving a picture of the village-life of Bengal, three centuries ago. It is at present being edited by a distinguished Bengali scholar and author, who tells me he finds his work very dull; happier times have robbed the poem of much of its appeal. For the poet lived in an unhappy age. In some respects, he is like a Bengali Langland, giving us his vision of Piers Plowman. The local Musalman rulers practised great oppression, and the people felt wretched and helpless. It was natural for them to look for outside assistance, and the thoughts of the poet, their spokesman, turned to Chandi (Durga), the powerful goddess in whom the dreadful energy of Siva was active. In Chandi the beasts of the forest complain to the goddess that they are in terror of Kalaketu the hunter. Under the guise of their speeches and of Chandi's, the political state of Bengal is set out.

Today, men are feeling too proud to consent to be wretched or to despair.Rabindranath Tagore, as is well known, is no lover of Saktism; and, like many patriotic Bengalis, he feels that the time for such an attitude as Mukundarama's has passed. 'The poet was a poor man, and was oppressed. So his only refuge was in the thought of this capricious Power, who might suddenly fling down the highest and exalt the lowest.' It is interesting in this connection to notice that the great period of Sakta-poetry in Bengal was the end of the eighteenth century, when the country's fortunes had reached their lowest ebb."

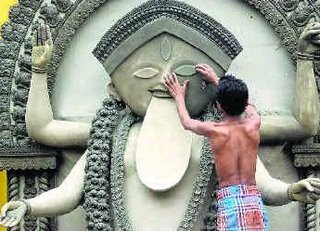

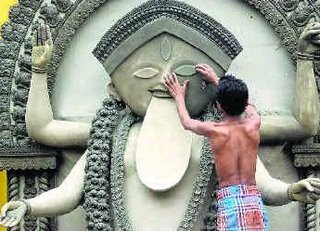

Sometime in the mid to late 16th century, Krishnananda Agamavagisa, a Bengali mystic (born after 1500) had an apocryphal powerful experience which resulted in a "new" form of Kali. It is said that Krishnananda went to bathe in a river near a cremation-ground (either at Tarapith or Bakreshwar, both in West Bengal), where he happened to stumble upon a dark-skinned tribal – probably Santhal -- girl who, believing she was alone, had stripped naked and was washing herself using a discarded skull-cap from a nearby funeral pyre. Her long black hair untied, and she was engrossed in her bathing, when some movement made her aware of the watching Krishnananda. Embarrassed the sudden gentleman intruder, she stuck out her tongue in shyness (a reflex action still done by village girls in India). Krishnananda, who had been trying to understand how best to comprehend the many varied forms of divinity, had a sudden and powerful mystical experience, he felt that the skies had opened and he had obtained a direct vision of the primordial female principle. He viewed this tribal girl as a living Kali, and took the "vision" of her naked dark body, long disheveled hair, extended tongue and skull in hand as a new and especially potent icon. The tribal girl symbolizes the hitherto marginalized animism in this story. For the rest of his life, Krishnananda evangelized this special form of Kali far and wide. Around 1580, he wrote the Tantrasara, an 'Essence of Tantras', in which he gave the following description of the Dark Goddess and which forms the basis of the typical Bengali Kali icon:

Possessed of complexion like the color of sapphire, blue like the sky, extremely fierce, defeating gods and demons, three- eyed, crying very loudly, decked with all ornaments, holding a human skull and a small sword, standing on the moon and sun.

Krishnananda also described other forms of Kali, named Dakshina Kali, Guhya Kali, Bhadra Kali, Smashana Kali and Maha Kali - meaning Right (or Southern) Kali, Secret Kali, Civil Kali, Cremation-ground Kali and Great Kali, probably thus synthesizing different regional/aboriginal/tantric cults. For instance Dakshina Kali is described by him as:

Loosened hair, garland of human heads, face with long or projecting teeth, four arms, lower left holding a human head just severed, upper left holding a sword, lower right hand posed as if giving a boon, the upper right hand posed granting freedom from fear, deep dark complexion, naked, two corpses or arrows as ornaments in the two ears, girdle of the hands of corpses, three eyes, radiant like the morning sun, standing on the chest of Mahadeva (Shiva) lying like a corpse, surrounded by jackals.

The dark goddess Kali also became known and revered in Tibet. Known there as Lhamo (God Mother), several different forms of Her are in the Tibetan pantheon. As the Great sickle-wielding all-powerful Queen Mother Goddess (dPal ldan dmag zor rgyal mo), She is the Guardian Goddess of Lhasa. She is also the Chief Protectress of the Gelugpa sect of Lamaism, of which the Dalai Lama is the supreme leader. She is the wrathful Protector of the Buddhist Dharma in Tibet, visualised at the base of the trunk of the lineage tree of several sects. She is the only feminine deity among the Buddhist Dharmapalas, the Defenders of the Law of Buddhism and one of her names, Sri Devi, tells of her Hindu origin. A two-armed form of Lhamo/Kali is described in a Tibetan text as follows:

The goddess is of dark blue hue, has one face, two hands, and rides on a mule. With her right hand she brandishes a huge sandalwood club adorned with a thunderbolt and with her left hand she holds in front of her breast the blood-filled skull of a child. She wears a flowing garment of black silk and a loincloth made of rough material. Her ornaments are a diadem of skulls, a garland of freshly-cut heads, a girdle of snakes, and bone ornaments, and her whole body is covered with the ashes of cremated corpses. She has three eyes, bares her fangs, and the hair on her head stands on end. She carries a sack of karmic things and a pair of dice. Among her retinue are countless black birds, black dogs and black sheep.

In various Tibetan Lhamo sadhana texts her names are given as Kali, Maha Kali, Dhumavati Devi, Chandika Devi, Remati, Shankapali Devi, and of course Tara, all of which are found in Hindu Tantra.

Just as Buddhism accommodated the rise of Kali, so, over the next two centuries, did Brahminism; Kali was slotted into the pantheon as a consort of Shiva, just another form of Durga. Perhaps in this she regained her place – both Shiva (Pashupati or Lord of Beasts) and Durga (Fortress Goddess) are immensely old and had had to be Aryanized for the religion of Indra and Mithra to make headway into the subcontinent. The seeds planted by Krishnananda thus gestated and seem to have blossomed in the early eighteenth century. One of the reasons scholars give for this upsurge in Kali's popularity is that she was the protective deity of the thugee robbers who held sway over large parts of the Bengal countryside in an era when central Mughal power was weakening. Kings like Krishnachandra Ray of Krishnanagar induced their subjects to worship Kali as well.

Kali is the form of the primordial Mother Goddess which symbolizes Shakti – Power -- as well as Destruction. She has Her origins in India's archaic matriarchal culture. Her radiant blackness came from the dark-skinned tribes who worshipped Her to instill fear and dread in their enemies. She was worshipped with blood sacrifice, and offerings of flesh and liquor. She was All-Powerful, awesome, mysterious as the night, fierce, the sensual and demanding Mother, also an all-merciful Protectress, the Cosmic Female Power, always available for Her devotees, ready to remove their suffering, their fear of time (Kala), who lived in the burning ghats, ready to receive her children back into her womb at the funeral pyre.

Hear me child, and know Me for who I am. I have been with you since you were born, and I will stay with you until you return to Me at the final dusk.

I am the passionate and seductive lover who inspires the poet to dream.

I am the One who calls to you at the end of your journey. After the day is done, My children find their blessed rest in My embrace.

I am the womb from which all things are born.

I am the shadowy, still tomb; all things must come to Me and bare their chests to die and be reborn to the Whole.

I am the Sorceress that will not be ruled, the Weaver of Time, the Divulgeress of Mysteries. I snip the threads that bring My children home to Me. I slit the throats of the cruel and drink the blood of the heartless. Swallow your fear and come to Me, and you will discover true beauty, strength, and courage.

I am the fury which rips the flesh from injustice.

I am the glowing forge that transforms your inner demons into tools of power. Open yourself to My embrace and become part of the light that is in the darkness.

I am the glinting sword that protects you from harm.

I am the crucible in which all the aspects of yourself merge in a rainbow of union.

I am the velvet depths of the night sky, the swirling mists of midnight, shrouded in mystery.

I am the chrysalis in which you will face that which terrifies you and from which you will blossom forth, vibrant and renewed. Seek Me at the crossroads of Life and Death, and you shall be transformed, for once you look upon my face, there is no return.

I am the fire that kisses the shackles away.

I am the cauldron in which all opposites grow to know each other in Truth.

I am the web which connects all things.

I am the Healer of all wounds, the Warrior Mother who rights all wrongs in their Time. I make the weak strong. I make the arrogant humble. I raise up the oppressed and empower the disenfranchised. I am Justice. I am Mercy. I am the End, and in that I am also the Beginning.

Most importantly, child, I am you. I am part of you, and I am within you. Seek Me within and without, and you will be strong. Know Me. Venture into the dark so that you may awaken to Balance, Illumination, and Wholeness. Take My Love with you everywhere and find the Power within to be who you wish.

Ur-Kali as a primal female principle can be found in many ancient cultures outside India, suggesting that in the distant past a common or related matriarchical religion pervaded much of the world. In pre-christian Ireland people worshipped a powerful goddess known as Kele (her priestesses were known as Kelles), from which the surname Kelly is descended. In ancient Finland there was the all-powerful smelly goddess of death and decay Kal-ma, and in the Sinai region of the Middle East there was the goddess Kalu. Kalu was associated with the new moon or amavasya -- lunar periods were called kalends in the ancient Mediterranean. This is one of the origins of calendar. It is likely that these are the result of the interplay of spiritual ideas and practices between India, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete and Greece before 1500 BC.

With Aryan and thereafter Buddhist dominance, dark Kali was the goddess of defeated peoples. She remained, however, in the substratum, part of the aboriginal demonolatry and the Tantric occult, and slept on in the names of places like Vajrajogini. The current representation of Kali is relatively new. In the 15th-16th centuries, the flow of the Ganges shifted towards East Bengal, via the Padma to the Bay of Bengal; this opened up a new settlement frontier to which were attracted itinerants – who tended to be from the ‘lower’ social strata than the Brahmano-Buddhist establishment. At the same time, Muslim power in Bengal changed hands from the Afghans to the Mughals. This consolidation of a foreign religion cut off the Brahmanical religion from state funding; the Buddhist establishment in Bengal had been destroyed earlier by the Afghans. As Aryan and Buddhist dominance receded, Kali emerged from the subterranean cultural memory of the slash-burn pastoralists, the hunters, the woodsmen, the tribal smiths and stonesmen who flocked to the new Bengal frontier.

Some of the aspects of Kali also reflect the despair felt at the Muslim consolidation. Thompson and Spencer in their Bengali Religious Lyrics say:

"The worship of Durga and Kali is perhaps most deeply rooted in Bengal, as has already been indicated. I think it would not be hard to find reasons for this. Take the case of Mukundarama, known as Kavikankan or 'gem of poets,' who finished his chief poem, the epic Chandi in 1589. This poem lives today mainly for its value as giving a picture of the village-life of Bengal, three centuries ago. It is at present being edited by a distinguished Bengali scholar and author, who tells me he finds his work very dull; happier times have robbed the poem of much of its appeal. For the poet lived in an unhappy age. In some respects, he is like a Bengali Langland, giving us his vision of Piers Plowman. The local Musalman rulers practised great oppression, and the people felt wretched and helpless. It was natural for them to look for outside assistance, and the thoughts of the poet, their spokesman, turned to Chandi (Durga), the powerful goddess in whom the dreadful energy of Siva was active. In Chandi the beasts of the forest complain to the goddess that they are in terror of Kalaketu the hunter. Under the guise of their speeches and of Chandi's, the political state of Bengal is set out.

Today, men are feeling too proud to consent to be wretched or to despair.Rabindranath Tagore, as is well known, is no lover of Saktism; and, like many patriotic Bengalis, he feels that the time for such an attitude as Mukundarama's has passed. 'The poet was a poor man, and was oppressed. So his only refuge was in the thought of this capricious Power, who might suddenly fling down the highest and exalt the lowest.' It is interesting in this connection to notice that the great period of Sakta-poetry in Bengal was the end of the eighteenth century, when the country's fortunes had reached their lowest ebb."

Sometime in the mid to late 16th century, Krishnananda Agamavagisa, a Bengali mystic (born after 1500) had an apocryphal powerful experience which resulted in a "new" form of Kali. It is said that Krishnananda went to bathe in a river near a cremation-ground (either at Tarapith or Bakreshwar, both in West Bengal), where he happened to stumble upon a dark-skinned tribal – probably Santhal -- girl who, believing she was alone, had stripped naked and was washing herself using a discarded skull-cap from a nearby funeral pyre. Her long black hair untied, and she was engrossed in her bathing, when some movement made her aware of the watching Krishnananda. Embarrassed the sudden gentleman intruder, she stuck out her tongue in shyness (a reflex action still done by village girls in India). Krishnananda, who had been trying to understand how best to comprehend the many varied forms of divinity, had a sudden and powerful mystical experience, he felt that the skies had opened and he had obtained a direct vision of the primordial female principle. He viewed this tribal girl as a living Kali, and took the "vision" of her naked dark body, long disheveled hair, extended tongue and skull in hand as a new and especially potent icon. The tribal girl symbolizes the hitherto marginalized animism in this story. For the rest of his life, Krishnananda evangelized this special form of Kali far and wide. Around 1580, he wrote the Tantrasara, an 'Essence of Tantras', in which he gave the following description of the Dark Goddess and which forms the basis of the typical Bengali Kali icon:

Possessed of complexion like the color of sapphire, blue like the sky, extremely fierce, defeating gods and demons, three- eyed, crying very loudly, decked with all ornaments, holding a human skull and a small sword, standing on the moon and sun.

Krishnananda also described other forms of Kali, named Dakshina Kali, Guhya Kali, Bhadra Kali, Smashana Kali and Maha Kali - meaning Right (or Southern) Kali, Secret Kali, Civil Kali, Cremation-ground Kali and Great Kali, probably thus synthesizing different regional/aboriginal/tantric cults. For instance Dakshina Kali is described by him as:

Loosened hair, garland of human heads, face with long or projecting teeth, four arms, lower left holding a human head just severed, upper left holding a sword, lower right hand posed as if giving a boon, the upper right hand posed granting freedom from fear, deep dark complexion, naked, two corpses or arrows as ornaments in the two ears, girdle of the hands of corpses, three eyes, radiant like the morning sun, standing on the chest of Mahadeva (Shiva) lying like a corpse, surrounded by jackals.

The dark goddess Kali also became known and revered in Tibet. Known there as Lhamo (God Mother), several different forms of Her are in the Tibetan pantheon. As the Great sickle-wielding all-powerful Queen Mother Goddess (dPal ldan dmag zor rgyal mo), She is the Guardian Goddess of Lhasa. She is also the Chief Protectress of the Gelugpa sect of Lamaism, of which the Dalai Lama is the supreme leader. She is the wrathful Protector of the Buddhist Dharma in Tibet, visualised at the base of the trunk of the lineage tree of several sects. She is the only feminine deity among the Buddhist Dharmapalas, the Defenders of the Law of Buddhism and one of her names, Sri Devi, tells of her Hindu origin. A two-armed form of Lhamo/Kali is described in a Tibetan text as follows:

The goddess is of dark blue hue, has one face, two hands, and rides on a mule. With her right hand she brandishes a huge sandalwood club adorned with a thunderbolt and with her left hand she holds in front of her breast the blood-filled skull of a child. She wears a flowing garment of black silk and a loincloth made of rough material. Her ornaments are a diadem of skulls, a garland of freshly-cut heads, a girdle of snakes, and bone ornaments, and her whole body is covered with the ashes of cremated corpses. She has three eyes, bares her fangs, and the hair on her head stands on end. She carries a sack of karmic things and a pair of dice. Among her retinue are countless black birds, black dogs and black sheep.

In various Tibetan Lhamo sadhana texts her names are given as Kali, Maha Kali, Dhumavati Devi, Chandika Devi, Remati, Shankapali Devi, and of course Tara, all of which are found in Hindu Tantra.

Just as Buddhism accommodated the rise of Kali, so, over the next two centuries, did Brahminism; Kali was slotted into the pantheon as a consort of Shiva, just another form of Durga. Perhaps in this she regained her place – both Shiva (Pashupati or Lord of Beasts) and Durga (Fortress Goddess) are immensely old and had had to be Aryanized for the religion of Indra and Mithra to make headway into the subcontinent. The seeds planted by Krishnananda thus gestated and seem to have blossomed in the early eighteenth century. One of the reasons scholars give for this upsurge in Kali's popularity is that she was the protective deity of the thugee robbers who held sway over large parts of the Bengal countryside in an era when central Mughal power was weakening. Kings like Krishnachandra Ray of Krishnanagar induced their subjects to worship Kali as well.

1 Comments:

Hi, I just read your post, and it is a very good introduction to Kali who is so often misunderstood. I actually just wrote a poem about Kali today which you can view here...

Post a Comment

<< Home