The Chaucer of the Turks

Izzat bermas naqdu diram borlig'i,

Kim bo'ldi tama'din kishining xorlig'i.

He who has lowered himself for gain,

Wealth can never raise up again.

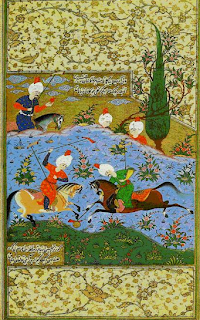

Mir Ali-Sher Beg Herawi "Nava'i" (Nawa'i, Navoi, or Navoiy; the takhallus meaning, roughly, melodious lamenter) lived from 1441 to 1501, i.e. he was a contemporary of Kabir. Nava'i is credited with the creation of Turkish literature. Chaucer, living at a time when the languages of culture and commerce were French and Latin, and also thriving as an insider in a world that discoursed in those languages (he was at various times valet to Edward III, Comptroller of the Port of London, and secret envoy of Richard II), had created a new medium -- of writing in the vernacular of the common folk of taverns and bath-houses, a medium that we now call Middle English. So, too, Nava'i, consummate Timurid courtier and classmate of the Sultan, abjured the dominant Farsi and Arabic languages to write in the everyday Chagatai Turkish of Turkestani bazaar and the mohalla. Contemporary Uzbek, the successor language to Chagatai Turkish, considers him to be a founding infuence (the comparison to Chaucer is due to Bernard Lewis). After Amir Timur and Bobur Mirza, few historical figures are endowed with as much official prestige as Nava'i in today's Uzbekistan: cities, universities, roads, bus-stations named after him abound all over the land. (You may also encounter him in Rushdie's novel about the Enchantress of Florence.)

I'm not Khusrau, nor wise Nizami,

Not the Sheikh of poets today - Jami.

But in my humility say:

In their famous walking paths let

Nizami's victorious mind run.

He won - Byrd, Ganja and Rum;

In the Hindvi tongue Khusrau can,

Conquer entire Hindustan;

Let all Iran sing Jami,

In Arabia, "Jami" beat the timpani

But the Turks! all tribes, of any country, all

Turks conquered me alone ...

Wherever there was a Turk,

Under the banner of Turkic words

I volunteered to be always ready.

And this tale of grief and separation,

Passion and torment, in spite of adversity,

I set out in the tongue of the Turk.

Nava'i's testament to Chagatai Turkish is his 1499 essay Muhakamat al-Lughatayn (Judgment between the Two Languages). Nava'i starts by saying there are four main languages, "each having many arms and branches": Arabic, Hindi, Turkish and Persian. As a godfearing mussulman, he does not want to say anything against Arabic: "Of all languages, Arabic possesses the most eloquence and grandeur, and there is no one who thinks or claims differently." As for Hindi, he dismisses it, saying it sounds like "the scratching of a broken pen", and when written it looks like the "footprints of crows". That leaves Turkish and Persian, the two languages spoken throughout Khorasan and Mawarannahr:

The beginner, upon encountering difficulty in composing, shuns Turkish and changes to an easier road (i.e., Persian). After this has happened several times it becomes habit; and after it has become habit the poet finds it difficult to abandon the habit in order to venture down a more difficult road. Later, other beginners, noting the conduct and the compositions of those who have preceded them, do not consider it proper to stray off that road. The result is that they too write their poems in Persian.

It is natural for a beginner to wish his works to be known to others. He wishes to submit them to scholars. But these are Persian-speakers who are not acquainted with Turkish, and this thought makes the poet shrink. Thus he is drawn to the use of Persian. He establishes relations with others and becomes one of them. This is how the present situation has come to be.

But, Nava'i says, in spite of obstacles and snares, poets of Turkish origin must strive to write in Turkish, they will surely experience the discovery of the splendors of their native tongue:

It is unfortunately true that the greater superiority, profundity and breadth of Turkish as compared to Persian as a medium for poetry has not been realized by everyone... In the early days of my youth I began to perceive a few jewels from the inkwell of my mouth. These jewels had not yet become a string of verse, but jewels from the sea of consciousness which were worthy of being placed on a string of verse began to reach shore, thanks to the nature of the diver.

Then I reached the age of comprehension and God (whose praises I recite and who be extolled!) instilled in me sensitivity and attentiveness and a desire for the unique. I realized the necessity of giving thought to Turkish words. The world which came into view was more sublime than 18,000 worlds, and its adorned sky, which I came to know, was higher than nine skies. There I found a treasury of superiority and excellence in which the pearls were more lustrous than the stars. I entered the rose garden. Its roses were more splendid than the stars of heaven, its hallowed ground was untouched by hand or foot, and its myriad wonders were safe from the touch of other hands.

Timur's son Shahrukh had, under the influence of the Persian 'slave girl' Goharshad, forsaken the Turkic homelands of Transoxiana to set himself up as first the governor, and then the ruler, of Khorasan. His capital was Herat; and the dominant culture in Herat throughout the first half of the 15th century was that of Persia. Shahrukh officers, as well many leading citizens, were Turks; but they were Turks bowled over by the splendid achievements of Persian civilization, there for all to see in the form of art, architecture, calligraphy, poetry, speech, courtliness and custom. The Turks, still only a century of two away from the rough and tumble of the steppe, were mesmerized by the radiance of Persia.

In this environment Nava'i was born. His father, Ghiyāth ud-Din Kichkina ("the Little"), served as a high-ranking officer in the palace of Shahrukh Mirza; his mother was governess to the royal princes. This cohort included Ulugh Beg (till he was prized away by Timur from the softening influences of Herat, to the tough life of campaigns on the saddle befitting a future monarch), and more importantly Sultan-Husayn Mirza (also known as Husain Baiqara), the future sultan of Khorasan, who was Nava'i's classmate at school. Babur describes Nava'i admiringly as a writer of Chagatai (in which language the Baburnama is also written), and also somewhat dismissively as a sidekick 'beg' of Sultan-Husayn. Nava'i's family came from a long line of Bakhshis, originally scribes and heralds of the Mongols, who joined the Timurid courts as finance officials. When Kichkina died, Shahrukh's son Bayshunghur's son Babur ibn-Bayshunghur became Nava'i's guardian. His life, therefore, was one of the highest privilege; he was taught by Jami, and when his fellow-student Sultan-Husayn became the king, he was appointed to the innermost circle.

Kamol et kasbkim, olam uyidin.

Senga farz o'lmagay g'amnok chiqmoq.

The only way to decrease one's sufferings

Is to increase one's understanding.

Agar naf'din bo'lsa mahzan yiroq,

Aning la'lidin xora ko'p yaxshiroq.

Better the cobble that paves the way

Than a gem locked away from the light of day.

Oz-oz o'rganib dono bo'lur,

Qatra-qatra yig'ilib daryo bo'lur.

Learning is knowledge acquired in small portions,

As drops make the rivers that flow to the oceans.

Also:

Do people get pleasure without offense?

How does the candle light taking not pains?

A tulip-egg stuck in soil becomes a full bloom,

A worm was like silk having gone to its doom.

As the small tulip egg, have you got any zeal,

Are not you kind as the worm full in silk?

Seek from others the knowledge they own,

Never rely on thy powers alone.

Spurn the company of those whose talk is vain,

But give ear to the wise again and again.

A hard-earned coin is better by far

Than unearned riches bestowed by the Shah.

Reading some of Nava'i's epigrammatic verse, I was made to think of Kabir's dohas. Kabir lived from 1440 to 1518, as much an outsider as Nava'i was an insider. Abandoned as an infant, he was found and raised by Niru, a muslim weaver living in Varanasi. One morning, as the bhakti saint Ramananda walked to the Ganges for his dawn bath, the little Kabir sleeping huddled on the ghat reached out and involuntarily grabbed the saint's feet, who called out "Ram, Ram" in response. Thus did Kabir get a guru.

Raat gawaayo soy kar, diwas gawaaya khai.

Heera janam amol tha, kaori badle jay.

The nights were lost in sleeping, in eating were lost the days

This priceless diamond life, slowly into a cowrie decays

Jeevat samjhe jeevat bujhe, Jeevat he karo aas

Jeevat karam ki fansi aa kaati, Mue mukti ki aas

Alive one sees, Alive knows, crave ye for salvation when still alive

Alive ye didn't cut loose bondage, yet hope for liberation on death?

Kabira garv na keejiye, uncha dekh aavaas

Kaal paron bhuin letna, uper jamsi ghaas

Says Kabir: Be not proud and vain, looking at your high mansion

Tomorrow you'll be laid in earth, grass growing thereon

Kabir did not become a sadhu, nor did he ever abandon worldly life, choosing to live in the world, householder and mystic, weaver and poet. Lately, with the growth in the ranks of doctoral students combing though archives for their dissertations, it has not been easy for the great to entirely retain their lustre. It is getting some attention that the symbol of the coarse woolen cloak that wraps the Sufi is often in contrast with the economic status of the Sufi shaykh himself. In her book the Mystical Dimensions of Islam, Annemarie Schimmel (German orientalist, Harvard professor, and Sitara-e-Imitiaz awardee in Pakistan) asks "how so many people who preached poverty as their pride became wealthy landlords and fitted perfectly into the feudal system, amassing wealth laid at their feet by poor, ignorant followers"?

In the Baburnama, Babur writes thus of Sultan-Husayn Mirza's wazirs:

One was Majdu'd-din Muhammad, son of Khwaja Pir Ahmad of Khwaf, the one man of Shahrukh Mirza's Finance-office. In SI. Husain Mlrza's Finance-office there was not at first proper order or method ; waste and extravagance resulted; the peasant did not prosper, and the soldier was not satisfied. Once while Majdu'd-din Muhammad was still parwanchi and styled Mirak (Little Mir), it became a matter of importance to the Mirza to have some money; when he asked the Finance-officials for it, they said none had been collected and that there was none. Majdu'd-din Muhammad must have heard this and have smiled, for the Mirza asked him why he smiled; privacy was made and he told Mirza what was in his mind.

Said he, "If the honoured Mirza will pledge himself to strengthen my hands by not opposing my orders, it shall so be before long that the country shall prosper, the peasant be content, the soldier well-off, and the Treasury full." The Mirza for his part gave the pledge desired, put Majdu'd-din Muhammad in authority throughout Khurasan, and entrusted all public business to him. He in his turn by using all possible diligence and effort, before long had made soldier and peasant grateful and content, filled the Treasury to abundance, and made the districts habitable and cultivated. He did all this however in face of opposition from the begs and men high in place, all being led by 'Ali-sher Beg (i.e. Nava'i), all out of temper with what Majdu'd-din Muhammad had effected. By their effort and evil suggestion he was arrested and dismissed.

The opposition made by Nava'i to reform so clearly to his patron's gain, and to his patron's courtiers' loss, begs the question, "What was the source of his own income? " It has been observed that Nava'i "through high positions occupied in the government of his country, had acquired a large fortune", and Nava'i clearly took a dim view of the "rights" of the cultivator. The Soviets must not have read the Baburnama too closely, since the city of Kermine in central Uzbekistan was renamed after the socialist hero Navoiy in 1958. Today, more appropriately, it is a free industrial economic zone.

Here is an extract from Chaucer's The Summoner's Tale. A friar is taken by the angel to Hell, to get a view of what pains lay there. He does not see a single friar in the place, and is perplexed -- are all the learned men full of grace?

In al the place saugh he nat a frere;

Of oother folk he saugh ynowe in wo.

Unto this angel spak the frere tho:

Now, sire, quod he, han freres swich a grace

That noon of hem shal come to this place?

Yis, quod this aungel, many a millioun! "

And unto sathanas he ladde hym doun.

--And now hath sathanas,--seith he,--a tayl

Brodder than of a carryk is the sayl.

Hold up thy tayl, thou sathanas!--quod he;

--shewe forth thyn ers, and lat the frere se

Where is the nest of freres in this place!--

And er that half a furlong wey of space,

Right so as bees out swarmen from an hyve,

Out of the develes ers ther gonne dryve

Twenty thousand freres on a route,

And thurghout helle swarmed al aboute,

And comen agayn as faste as they may gon,

And in his ers they crepten everychon.

He clapte his tayl agayn and lay ful stille.

Translation from wikipedia:

In all the place he saw not a friar;

Of other folk he saw enough in woe.

Unto this angel spoke the friar thus:

"Now sir", said he, "Have friars such a grace

That none of them come to this place?"

Yes", said the angel, "many a million!"

And unto Satan the angel led him down.

"And now Satan has", he said, "a tail,

Broader than a galleon's sail.

Hold up your tail, Satan!" said he.

"Show forth your arse, and let the friar see

Where the nest of friars is in this place!"

And before half a furlong of space

Just as bees swarm out from a hive

Out of the devil's arse there were driven

Twenty thousand friars on a rout,

And throughout hell swarmed all about,

And came again as fast as they could go

And every one crept into his arse,

He shut his tail again and lay very still.

Below, Nava'i's verse set to music. The first part of the Soviet propaganda biopic is here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home