Giovanni da Pian del Carpine

|

Historians regard the Mongol raids and invasions - of Europe as well of Transoxiana and Baghdad - as some of the deadliest conflicts in human history. It has been said that the Mongols brought terror on a scale not seen again until the world wars and wars of imperialism of the 20th century. It has also been said that the Mongol invasions induced population displacement on a scale never seen before. While Europe was being invaded, however, the Great Chingis Khan had died in December 1241, and upon hearing the news in 1242, all princes of the blood rushed back to Mongolia to elect a new Khan; so there was a lull in the sack of Europe.

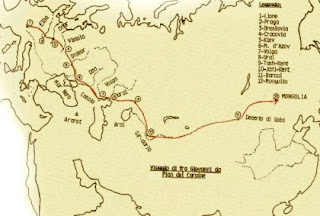

During this lull, fear and trepidation were the main currency among the courts of Eastern Europe. In 1245, Pope Innocent IV dispatched two Franciscans, Lawrence of Portugal and John of Plano Carpini, to travel to the Mongol, or 'Tartar' as the Christians called them, kingdom. This journey is recounted by Friar John in his work, History of the Mongols, and also reported by later travelers. John had travelled widely through Mongol lands a decade before Marco Polo was even born.

Friar John, or Giovanni da Pian del Carpine as his name is written in Italian, was an old man - around 65 at the time. As a papal legate, he bore a letter from the Pope to the Great Khan. Behind his mission there may also have been the stirrings of a new policy - converting these wolf-worshipping Mongols to Christianity, followed by harnessing their military prowess to create a joint front against Islam.

Starting from Lyon (where the Pope was then resident) on Easter day of 1245, John was joined at Wrocław by Benedykt Polak, another friar, appointed to act as interpreter. Their route passed by Kiev, entered the 'Tatar' posts at Kaniv, and then ran across the Nepere to the Don and Volga - John is the first European to give us the modern names for these rivers. On the Volga stood the Ordu, or camp, of Batu, the notorious destroyer of Eastern Europe and supreme Mongol commander on the western frontiers of the empire. Here the envoys had to pass between two fires to remove possible injurious thoughts and poisons, before being presented to Batu Khan at the beginning of April 1246.

For a monk, John turned out to be a quite astute student of war; he describes the ways the Mongols conduct war, as well as giving advice on how they could be successfully fought when they resumed their invasion of Europe.

These men, that is to say the Tartars, are more obedient to their masters than any other men in the world, be they religious or seculars; they show great respect to them nor do they lightly lie to them. They rarely or never contend with each other in word, and in action never. Fights, brawls, wounding, murder are never met with among them. Nor are robbers and thieves who steal on a large scale found there; consequently their dwellings and the carts in which they keep their valuables are not secured by bolts and bars. If any animals are lost, whoever comes across them either leaves them alone or takes them to men appointed for this purpose; the owners of the animals apply for them to these men and they get them back without any difficulty. They show considerable respect to each other and are very friendly together, and they willingly share their food with each other, although there is little enough of it. They are also long-suffering. When they are without food, eating nothing at all for one or two days, they do not easily show impatience, but they sing and make merry as if they had eaten well. On horseback they endure great cold and they also put up with excessive heat. Nor are they men fond of luxury; they are not envious of each other; there is practically no litigation among them. No one scorns another but helps him and promotes his good as far as circumstances permit.

They are quickly roused to anger with other people and are of an impatient nature; they also tell lies to others and practically no truth is to be found in them. At first indeed they are smooth-tongued, but in the end they sting like a scorpion. They are full of slyness and deceit, and if they can, they get round everyone by their cunning. They are men who are dirty in the way they take food and drink and do other things. Any evil they intend to do others they conceal in a wonderful way so that the latter can take no precautions nor devise anything to offset their cunning. Drunkenness is considered an honorable thing by them and when anyone drinks too much, he is sick there and then, nor does this prevent him from drinking again. They are exceedingly grasping and avaricious; they are extremely exacting in their demands most tenacious in holding on to what they have and most niggardly in giving. They consider the slaughter of other people as nothing. In short, it is impossible to put down in writing all their evil characteristics on account of the very great number of them.

Their food consists of everything that can be eaten, for they eat dogs, wolves, foxes and horses and, when driven by necessity they feed on human flesh. For instance, when they were fighting against a city of the Khitayans, where the Emperor was residing, they besieged it for so long that they themselves completely ran out of supplies and, since they had nothing at all to eat, they thereupon took one out of every ten men for food. They eat the filth which comes away from mares when they bring forth foals. Nay, I have even seen them eating lice. They would say, "Why should I not eat them since they eat the flesh of my son and drink his blood?" I have also seen them eat mice.

Chingis Khan divided his Tartars by captains of ten, captains of a hundred, and captains of a thousand, and over ten millenaries, or captains of a thousand, he placed one colonel, and over one whole army he authorized two or three chiefs, but so that all should be under one of the said chiefs. When they join battle against any other nation, unless they do all consent to retreat, every man who deserts is put to death. And if one or two, or more, of ten proceed manfully to the battle, but the residue of those ten draw back and follow not the company, they are in like manner slain. Also, if one among ten or more be taken, their fellows, if they fail to rescue them, are punished with death.

Moreover they are required to have these weapons: two long bows or one good one at least, three quivers full of arrows, and one axe, and ropes to draw engines of war. But the richer have single-edged swords, with sharp points, and somewhat crooked. They have also armed horses, with their shoulders and breasts protected; they have helmets and coats of mail. Some of them have jackets for their horses, made of leather artificially doubled or trebled, shaped upon their bodies. The upper part of their helmet is of iron or steel, but that part which circles about the neck and the throat is of leather. Some of them have all their armor of iron made in the following manner: They beat out many thin plates a finger broad, and a hand long, and making in every one of them eight little holes, they lace through three strong and straight leather thongs. So they join the plates one to another, as it were, ascending by degrees. Then they tie the plates to the thongs, with other small and slender thongs, drawn through the holes, and in the upper part, on each side, they fasten one small doubled thong, that the plates may firmly be knit together. These they make, as well for their horses as for the armor of their men; and they scour them so bright that a man may hold his face in them. Some of them upon the neck of their lance have a hook, with which they attempt to pull men out of their saddles. The heads of their arrows are exceedingly sharp, cutting both ways like a two-edged sword, and they always carry a file in their quivers to sharpen their arrowheads.

No one kingdom or province is able to resist the Tartars; because they use soldiers out of every country of their dominions. If the neighboring province to that which they invade will not aid them, they waste it, and with the inhabitants, whom they take with them, they proceed to fight against the other province. They place their captives in the front of the battle, and if they fight not courageously they put them to the sword. Therefore, if Christians would resist them, it is expedient that the provinces and governors of countries should all agree, and so by a united force should meet their encounter.

Soldiers also must be furnished with strong hand-bows and cross-bows, which they greatly dread, with sufficient arrows, with maces also of strong iron, or an axe with a long handle. When they make their arrowheads, they must, according to the Tartars' custom, dip them red-hot into salt water, that they may be strong enough to pierce the enemies' armor. They that will may have swords also and lances with hooks at the ends, to pull them from their saddles, out of which they are easily removed. They must have helmets and other armor to defend themselves and their horses from the Tartars' weapons and arrows, and they that are unarmed, must, according to the Tartars' custom, march behind their fellows, and discharge at the enemy with long–bows and cross-bows. And, as it has already been said of the Tartars, they must dispose their bands and troops in an orderly manner, and ordain laws for their soldiers. Who–soever runs to the prey or spoil, before the victory is achieved, must undergo a most severe punishment. For such a fellow is put to death among the Tartars without pity or mercy.

The place of battle must be chosen, if it is possible, in a plain field, where they may see round about; neither must all troops be in one company, but in many, not very far distant one from another. They which give the first encounter must send one band before, and must have another in readiness to relieve and support the former in time. They must have spies, also, on every side, to give them notice when the rest of the enemy's bands approach. They ought always to send forth band against band and troop against troop, because the Tartar always attempts to get his enemy in the midst and so to surround him. Let our bands take this advice also; if the enemy retreats, not to make any long pursuit after him, lest according to his custom he might draw them into some secret ambush. For the Tartar fights more by cunning than by main force. And again, a long pursuit would tire our horses, for we are not so well supplied with horses as they. Those horses which the Tartars use one day, they do not ride upon for three or four days after. Moreover, if the Tartars draw homeward, our men must not therefore depart and break up their bands, or separate themselves; because they do this also upon policy, namely, to have our army divided, that they may more securely invade and waste the country. Indeed, our captains ought both day and night keep their army in readiness; and not to put off their armor, but at all time to be prepared for battle. The Tartars, like devils, are always watching and devising how to practice mischief. Furthermore, if in battle any of the Tartars be cast off their horses, they must be captured, for being on foot they shoot strongly, wounding and killing both horses and men.

Batu ordered John of Piano Carpini to proceed to the court of the Great Khan in Mongolia. The party was so ill, writes John, that the travelers could scarcely sit on a horse; and throughout all that Lent their food had been millet with salt and water, and with only snow melted in a kettle for drink. On Easter day once more in 1246, they started on the most formidable part of their journey across Central Asia. Their bodies were tightly bandaged so they could endure the excessive fatigue of this enormous ride, which took them across the Jaec or Ural River, and north of the Caspian Sea and past the Aral to the Jaxartes or Syr Darya (quidam fluvius magnus cujus nomen ignoramus, writes John, "a big river whose name we do not know"), and the cities of Bukhara and Samarkand that stood on its banks. Then they went along the shores of the Dzungarian lakes until, on the feast of St Mary Magdalene (22 July), they reached the imperial camp called Sira Orda (i.e., Yellow Pavilion), near Karakorum and the Orkhon River. The good Friar had ridden three thousand miles in a hundred days.

While John had been in transit, Ögedei Khan had also died, and the imperial authority was in interregnum; Güyük, Ögedei's eldest son, being designated to the throne. His formal election in a great Kurultai, or diet of the tribes, took place while the friars were at Sira Orda, along with 3000 to 4000 envoys and deputies from all parts of Asia and eastern Europe, bearing homage, tribute and presents. On the 24th of August, John's party witnessed the formal enthronement of Guyuk at another camp in the vicinity called the Golden Ordu, after which they were presented to the emperor.

The Great Khan Güyük, as we have seen, was not amused by the invitation to become Christian, and demanded, instead, that the Pope and rulers of Europe should come to him to swear allegiance. The Khan did not dismiss the Friar's expedition until November 1246. He gave them the letter to the Pope we have encountered earlier. John's party began a long winter journey home. They had to sleep on snow most of the crossing of Central Asia, and reached Kiev in June 1247, where they were greeted as if risen from the dead. Crossing the Rhine at Cologne, they found the Pope still at Lyon, and delivered their report as well as Güyük Khan's letter.

Below, we cross parts of the high Altaic steppe, similar in parts to what John travelled through on horseback circa 1246.

1 Comments:

I like more posts like this. Every time I get a valuable inspiration. Full marks to you. Keep it up and send us more blog posts.

Ukrainian interpreter

Post a Comment

<< Home