Srirangapatnam

I cannot express how delighted I am

To hear we have taken Seringapatam

The Chancellor look'd like a frolicsome Ram

To hear we had taken Seringapatam.

Dundas fled from bottle, from chicken and ham

To Windsor to tell of Seringapatam.

Will Pitt eat a cake with some raspberry jam

When told we had taken Seringapatam.

The Prince gave a nod to his Porter big Sam

You hear we have taken Seringapatam.

We are happy to find in this Victory sham,

Not an Englishman fall at Seringapatam.

The Vestal it seems had arrived in the Cam

With the news of the taking Seringapatam.

The mighty Tipoo from a battering ram

Got shot in the thigh at Seringapatam.

Pagodas, and cannon, beef, mutton and lamb,

Were found in the streets of Seringapatam.

Lord Cornwallis bestow'd on each Soldier a Dram,

For his gallant attack on Seringapatam.

Great George look'd as sapient as old Abraham

When he heard we had taken Seringapatam

The Stocks were forc'd up five per cent by the flam,

Of our having taken Seringapatam.

Now the People of England most heartily damn

The Wonderful News from Seringapatam!

Srirangapatnam lies on an island in the river Cauvery, and is the site of an immensely old stone temple dedicated to Lord Ranganatha (Vishnu) as well as the ruined capital of Haider Ali and his son Tipu Sultan. The temple was built by the Gangas in the 9th century AD, though the strategic nature of the island had made it into a religious refuge perhaps as much as a thousand years before this date. In the 10th-16th centuries, the temple was fortified and improved upon architecturally by the Hoysala and Vijaynagar rulers, resulting in a medley of styles. Hyder Ali is said to have made endowments to this temple, and Tipu is said to have prayed at the temple himself.

The town of Srirangam near Tiruchirapalli in Tamil Nadu is similar in that it is also on an island formed by the river Cauvery, and is the site of another important shrine dedicated to Lord Ranganatha. Along with Shivanasamudram and Srirangam, Srirangapatna forms a chain of three Ranganatha deities referred to as Adiranga (Srirangapatnam), Madhyaranga and Antyaranga (Srirangam) respectively; if one can visit all three in a day one apparently earns tremendous punya.

The first phase of the British conquest of India was driven by the greed of the officials of the East India Company. After Robert Clive had enticed Mir Jafar to betray Siraj-ud-daula at Plassey in 1757 and set up Mir Jafar on the throne of Bengal, he paid out £1,250,000 to himself and his cronies from the treasury of Bengal. Compounding this at 5% annually, the booty in today’s terms is about $300 billion, or Rs. 1350-lakh lakhs. Clive himself is supposed to have been astonished by his own ‘moderation’ in the whole exercise. Back home, the British people were often scandalized and jealous of these ‘nabobs’, “but in India where revenue extraction was the main business of government and where personal fortunes were not readily distinguished from official receipts, British rapacity attracted much less attention than it did in England.” (John Keay: “India, A History.”)

The second phase was perhaps driven by ambition. Cornwallis had arrived in India in 1786 from the disaster of the American revolution, where through a strategic blunder at Yorktown he had been compelled to surrender to Washington. The state of Anglo- Mysore relations seemed to be right for a reputation-redeeming war.

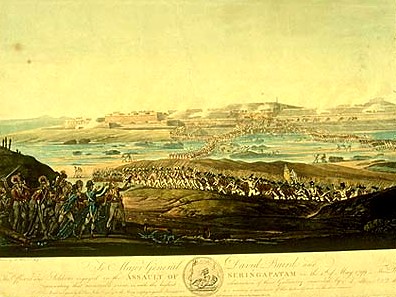

In the First Mysore War (1767) Haider Ali had driven the British back out of the Carnatic, and a 19 year-old Tipu had raided the very streets of Company-held Madras. In the Second Mysore War (1780-84), the British had attacked Mysore on two fronts, from Madras and from Bombay. The 4000-strong British invading force was annihilated, and its commander had to run away leaving his personal effects behind on field of battle. Into this situation, ripe, it would seem, for a turnaround, stepped Cornwallis. For the Third Mysore War, he stitched together an alliance with two sworn enemies of Mysore – the Marathas of Pune and the Nizam of Hyderabad, and besieged Srirangapatnam with 20,000 troops. Outnumbered, Tipu held out for a year before surrendering to humiliating terms – losing half his kingdom and agreeing to pay an indemnity of over a hundred lakh, and having his sons held as hostages with Cornwallis till that indemnity was paid. Contemporary public opinion in England, however, saw this a personal war of the ambitious and powerful; Richard Newton's satirical print, entitled 'Wonderful News from Seringapatam,' published in 1792 is quoted above.

A Scotsman, Major Dirom, who served in the Third Mysore War, published his comprehensive 'Narrative' of the campaign in 1793. In it, he describes the departure of Tipu’s young sons as hostages of the British:

'On the 26th about noon, the Princes left the fort, which appeared to be manned as they went out, and every where crouded (sic) with people, who, from curiosity or affection, had come to see them depart. The Sultan himself, was on the rampart above the gateway. They were saluted by the fort on leaving it, and with twenty-one guns from the park as they approached our camp, where the part of the line they passed, was turned out to receive them. The vakeels conducted them to the tents which had been sent from the fort for their accommodation, and pitched near the mosque redoubt, where they were met by Sir John Kennaway, the Mahratta and Nizam's vakeels, and from thence accompanied by them to head quarters.

The Princes were each mounted on an elephant richly caparisoned, and seated in a silver howder (sic), and were attended by their father's vakeels, and the persons already mentioned, also on elephants. The procession was led by several camel harcarras, and seven standard-bearers, carrying small green flags suspended from rockets, followed by one hundred pikemen, with spears inlaid with silver. Their guard of two hundred Sepoys, and a party of horse, brought up the rear. In this order they approached head quarters, where the battalion of Bengal Sepoys, commanded by Captain Welch, appointed for their guard, formed a street to receive them.'

'Lord Cornwallis, attended by his staff, and some of the principal officers of the army, met the Princes at the door of his large tent as they dismounted from the elephants; and, after embracing them, led them in, one in each hand, to the tent; the eldest, Abdul Kalick, was about ten, the youngest, Mooza-ud-Deen, about eight years of age. When they were seated on each side of Lord Cornwallis, Gullam Ally, the head vakeel, address his Lordship as follows. "These children were this morning the sons of the Sultan my master; their siutation is now changed, and they must look up to your Lordship as their father.'

Lord Cornwallis, who had received the boys as if they had been his own sons, anxiously assured the vakeel and the young Princes themselves, that every attention possible would be shewn to them, and the greatest care taken of their persons. Their little faces brightened up; the scene became highly interesting; and not only their attendants, but all the spectators were delighted to see that any fears they might have harboured were removed, and that they would soon be reconciled to their change of situation, and to their new friends.

The princes were dressed in long white muslin gowns, and red turbans. They had several rows of large pearls round their necks, from which was suspended an ornament consisting of a ruby and an emerald of considerable size, surrounded by large brilliants; and in their turbans, each had a sprig of rich pearls. Bred up from their infancy with infinite care, and instructed in their manners to imitate the reserve and politeness of age, it astonished all present to see the correctness and propriety of their conduct.'

(Tipu's sons leaving to becomes hostages – painting by Robert Home; The Storming of Seringapatnam by Sir Alexander Allan and Sir Robert Ker Porter.)

The Third Mysore War had wounded the tiger without killing him. It was only logical that a Tipu looking for revenge was not a good neighbor to have for Madras, Bombay or Hyderabad. In 1799, Wellesley broke the Anglo-Mysore treaty on the excuse that Tipu was corresponding with Napoleon, and attacked Srirangapatnam with 40,000 troops, and perhaps many times the number of helpers and auxiliaries requiring 100,000 bullocks for transport – “the largest ox-drawn baggage train ever composed”; in three months, “Srirangapatnam was stormed, then sacked with an ardor that would not have disgraced Attila.” (John Keay again.) The defenders amounting to some 9000 were killed, and the body of Tipu was found in the ruins, bayoneted, shot and robbed of his jewels and clothes. The first picture of this post shows the Gumbuz, under which he is buried along with his parents; the pictures below show Dariya Daulat Bagh, Tipu’s summer palace; and the spot where his mutilated body was found.

কি হল রে জান

পলাশীর মৈদানে উড়ে

কোম্পানির নিশান

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home