Two well lit malls which rival in decor, merchandise and facade anything in Singapore or Hong Kong. A congested road jam packed with autos and cars in the middle. An elephant ambling along. Here's an extract from an article in Time magazine from about an year ago:

" The glass and metal facade of the Sahara Mall in Gurgaon, a thriving township southwest of New Delhi, looks like a perfect emblem of the new India. Emblazoned with logos of clothing stores, gift shops and fast-food restaurants, the mall's glistening exterior seems to capture the exuberance of India's economic boom. Inside, however, except for a busy restaurant and supermarket, business is sluggish, and many shops are slathered with signs proclaiming SALE.

"The customer response has been far below our expectations," says Atul Kaushal, owner of Threads & Toes Mart, a shop that sells jeans and shoes. "Many people come to the mall to look around, but very few actually buy anything." Kaushal says he's just about breaking even, but in another part of the mall, the manager of a shoe store is even more downcast. "We've been here for a year and a half, and we're still not making a profit," he says. He points to his signs offering discounts of up to 50%. "We came to a mall to be a retail store, but instead we've turned into a discount shop," he says. Both for locals and for visitors from abroad, nothing seems to symbolize India's transformation from a stagnant third-world country into an emerging economic super-power as much as its sparkling new malls. American brand names like Levi's and McDonald's clutter the air-conditioned interiors, teenagers in low-cut jeans hang out in groups, cappuccino is sold at kiosks, and everyone appears to be having a great time. Eager to cash in, India's real estate developers are in a frenzy: up to 600 malls are likely to be up and running in India by the end of 2009—up from 20 malls this year—according to KSA Technopak, a New Delhi-based consulting firm. The capital is the epicenter of the boom, with as many as 100 malls—some estimates put the number at 150—planned for New Delhi and its vicinity in the next three years. There's only one hitch: many of these malls will struggle to make money.

"If all the planned malls do come up, 70% of them will fail," predicts Vikram Bakshi, managing director of McDonald's (Northern India), which is a prominent attraction in numerous Indian malls. Bakshi, who says McDonald's won't be present in 70-80% of the capital's new malls, points out a fundamental problem facing malls that are already operating around New Delhi: a lot of people come to see them and to enjoy the air-conditioned luxury, but not many spend money there. Usha Varadharajan, owner of The Next Shop, which sells gift items like crockery and soaps in the Centrestage Mall in Noida, another township near New Delhi, knows the phenomenon all too well. "Most people just walk in and walk out without buying a thing," she says. Standing outside her store, 17-year-old Ankur Malik, a teenager hanging out in the mall with a friend, agrees: "Eighty percent of young people come to a mall just to waste time. Actually, we're doing the same thing."

Scenes from the class struggle in Gurgaon:

http://www.indiatogether.org/2005/aug/psa-gurgaon.htm. At the street lights, women and children beg from the cars. Shunya asks one where she is from. Kota, Rajasthan. No water in anymore in the village, a group has come to Delhi to make money selling plaster Ganeshes, working odd jobs as construction workers, and making a little extra cadging at night. There is only one civil hospital in Gurgaon. Shunya took Shorifa's husband there to treat his peptic ulcers -- you join the queue at 8:30 and if you are lucky the doctor makes a 15 minute appearance at noon. In despair you go to the Dr. Bengali or Dr. Rajasthani who caters to the regional migrants. Saline packs are apparently a great favorite of the people -- and being given a drip is a true sign of getting western medicine. Irrespective of requirement, Dr. Bengali orders 5 saline pouches for the rickshaw-pullers and domestic workers -- Rs. 2500 in all. Added to that is a curious mish-mash of antibiotics, antihistamines, distilled water. No one has heard of cimetidine for ulcers. The power of belief systems -- allopathy -- no different from the blind faith reposed in 'organic.'

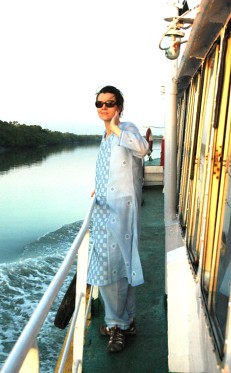

In a few hours, we leave for Calcutta on board the Rajdhani. More on the Doab next.